What is Brunello? It is pure Sangiovese from Montalcino. Aged for four years, of which at least two are in wooden barrels. It is the result of centuries of passion, experimentation, and successes. It is a Tuscan legend. It's all of this, but also much more. It is the living and vital expression of a community, a tradition, an identity. It is a chorus of hundreds of producers, with countless protagonists throughout the centuries. A thousand voices, but one extraordinary theme: Brunello di Montalcino.

The 1500s: The Name "Brunello" Is Born

The earliest mention of the name Brunello can be found in the 16th-century “Chronicle” by Marcantonio Rigaccini on page 22, where it states: “Renai and Martoccia are the two most famous vineyards of the time, producing the best Brunello di Montalcino.” Historian Leandro Alberti, in the “Descrittione di tutta Italia” from 1551, writes: “Walking towards Siena, one can spot atop a high hill, Monte Alcino, known as Mons Alcinoi by the Volaterrano, renowned in the region for the excellent wines cultivated on its pleasant hills.”

The 1600s: Brunello Becomes the Wine of the King of England and the Pope

During this period, “Montalcino is the only municipality in the area producing premium wine for the market...” Even the court of England imported Montalcino wines: between 1688 and 1712, King William III insisted they be served at his table, as documented in extensive correspondence between the English ambassador in Tuscany, Lord Evelyn, and the Court of St. James.

King William III. Between 1688 and 1712, the English court imported wines from Montalcino

King William III. Between 1688 and 1712, the English court imported wines from Montalcino

Economist and historian Federico Melis writes about Montalcino's wine production in “I vini italiani nel medioevo”: “Montalcino was already emerging—though the name Brunello started appearing only in the late 1500s.” From 1623 to 1644, Montalcino physician Giulio Mancini served as the Pope’s personal doctor and brought Montalcino wines as gifts to Pope Urban VIII. The wines were highly appreciated “for their strength and flavor,” so much so that the Pope “often discreetly requested them for himself and his court.” In the latter half of the 1600s, Montalcino wines were regularly exported to England, as evidenced by a text by Dante Vigiani published in 1943.

The 1700s and Early 1800s: Brunello Comes of Age

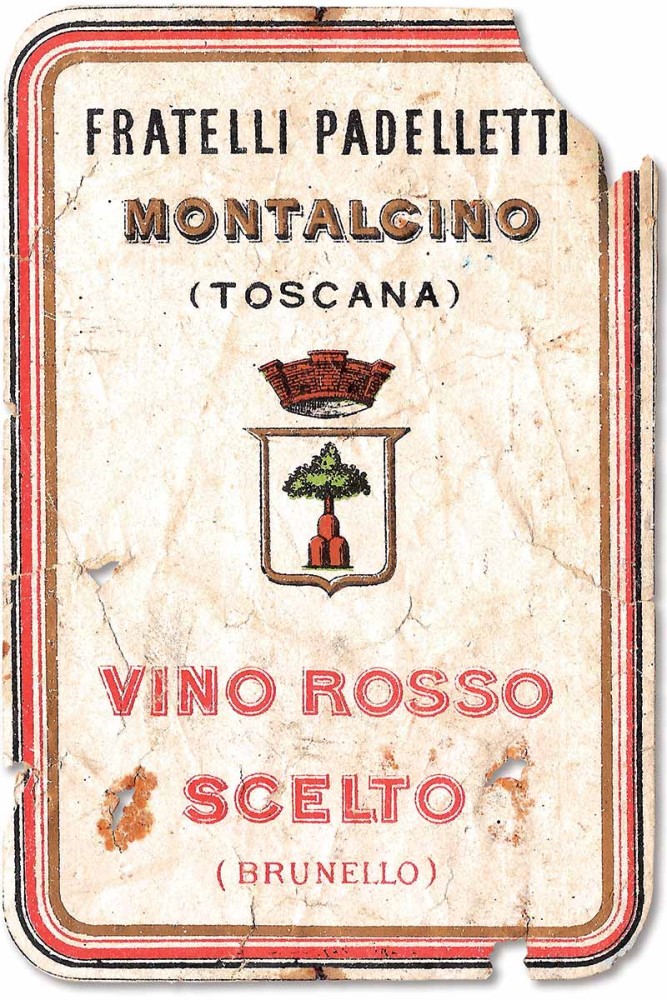

During this time, the only sector growing in Montalcino was wine production, increasing from 5,750 "some" in 1676 (equivalent to 700,000 bottles today) to over 5,000 hectares by the early 1800s. Today, there are 3,480 hectares. Around 1750, Giovanni Antonio Pecci wrote that “Montalcino sits atop a steep hill, which, if not for the labor and industry of the locals, would undoubtedly remain harsh and uninhabitable. But the frequent cultivation of vines and other domestic trees makes it pleasant.” In 1770, renowned naturalist Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti noted in Riflessioni sopra la poca durata dei vini toscani that Montalcino wines possessed excellent qualities and were among the few in Tuscany with great aging potential. From 1820, the Padelletti brothers began selling Brunello bottles with labels printed in typography, a precursor of a brighter future.

In 1834, esteemed agronomist Cosimo Ridolfi argued (as reported by Paolo Bellucci in I Lorena in Toscana) that contemporary wines were mediocre and unsuitable for export but should improve until all Tuscan wines gained recognition like “Chianti,” “Pomino,” “Carmignano,” and “Montalcino.” For Ridolfi, Brunello was among the four best Tuscan wines and should serve as an example. In 1856, Clemente Santi presented his wines at exhibitions in London and Paris.

From 1820, the Padelletti brothers started selling Brunello bottles with typographic labels

From 1820, the Padelletti brothers started selling Brunello bottles with typographic labels

1860 – 1918: Brunello Wins Accolades Across Europe

In 1869, Clemente, son of Luigi Santi, received a silver medal from the Agricultural Assembly of the Montepulciano District for a Brunello from 1865. In 1870, Tito Costanti, mayor of Montalcino, presented a Brunello 1865 at the Provincial Exhibition in Siena. Brunello consistently gained recognition, winning over 100 awards throughout Europe between 1860 and World War I. However, the emergence of phylloxera in 1888 challenged Montalcino's prosperous viticulture. The entire region had to replant vineyards with American rootstock to combat the parasite.

In 1870, Tito Costanti participated in the Provincial Exhibition of Siena with a wine labeled Brunello

In 1870, Tito Costanti participated in the Provincial Exhibition of Siena with a wine labeled Brunello

1919 – 1945: Brunello Lays the Foundation for the Future of Italian Wine

During this period, the municipality seemed destined for decline, with Brunello being the only factor growing, albeit slowly. Bottled quantities sold were still modest, but it was during this time that many ideas were implemented in Montalcino, laying the groundwork for the success of quality wine. In 1926, Tancredi Biondi Santi founded the Cantina Sociale Biondi Santi & C. under the ancient Hospital of St. Mary of the Cross (now the municipal headquarters), bringing together eight major producers who decided to vinify and bottle their wines collectively. Each producer could then sell or compete for awards under their own label. This concept remains innovative even today. In 1931, Fattoria dei Barbi sold Brunello by mail (the “internet” of that time) through a mailing list targeting lawyers and doctors across Italy, who purchased over 10,000 bottles annually. Shortly thereafter, Cantina Sociale Biondi Santi & C. shipped Brunello bottles to the USA, making them the first high-priced Italian wines sold in what would become major markets of the future. In 1933, ten Montalcino businesses participated in the first Market Exhibition of Typical Italian Wines in Siena, declaring a total production of 4,850 hectoliters, equivalent to 650,000 bottles—a huge quantity for the time. Not only did Brunello producers attend wine fairs even in the 1930s, but they did so collectively, forming one of the largest groups of exhibitors. Montalcino even had the event's motto, penned by poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti: “Brunello is fuel,” symbolizing the energy driving the world’s engine. The second-edition catalog from 1935 stated, “It is obtained from the vinification of only Brunello, now universally recognized as a sub-variety of Sangiovese Grosso.” In 1941, Mayor Giovanni Colombini inaugurated Italy’s first public wine shop in the ancient Fortress, which was regulated to sell only locally-produced agricultural products. Concepts such as local authenticity, zero-kilometer products, and leveraging cultural heritage to enhance local goods were ahead of their time.

In 1926, Tancredi Biondi Santi founded the Cantina Sociale Biondi Santi & C

In 1926, Tancredi Biondi Santi founded the Cantina Sociale Biondi Santi & C

1946 – 1969: The Post-War Crisis Threatens Brunello

All sectors of Montalcino’s economy were hit, and the collapse in each sector exacerbated the damage in others. Thus, a prosperous municipality became one of the poorest in Tuscany, losing 70% of its population in a few years. Only a handful of major estates that had shaped Brunello’s history survived, along with a few newly-founded family-run farms and small agricultural holdings, which were focused on cereal and livestock farming rather than winemaking. However, it was from these foundations that Montalcino began to build its recovery. In 1949, Fattoria dei Barbi established Tuscany's first winery always open to the public, offering tastings, bottle purchases, meals, and guided tours. In 1955, Giovanni Colombini and in 1957, Tancredi Biondi Santi hired Sienese painter and graphic designer Vittorio Zani (1892–1972) to design their new labels, which would become iconic symbols of Italian winemaking. These were strategic marketing operations paired with the development of modern sales networks in Italy and abroad and effective image policies, leading by the early 1970s to Greppo selling 10,000 bottles of Brunello and Barbi first to 100,000 and then to 200,000. At the time, these were extraordinary figures for quality wines and the highest in Italy. In 1961, Veronelli's “I Vini d’Italia” was published, identifying Brunello as Italy’s best wine for red meats. In 1963, the DOC (Controlled Designation of Origin) was established, and in 1966, Brunello became the first red wine among the top ten DOCs. Fourteen years later, it would be the first DOCG, the highest official recognition the Italian State can grant. In 1967, eighteen producers founded the Brunello Wine Consortium. Official recognitions for Brunello were in place, sales and popularity were growing rapidly, but the crisis was still severe. The number of winegrowers had dwindled to 37, with only 105 hectares registered for Brunello, and of the many pre-war producers, only three were still selling bottled Brunello. By 1969, Veronelli published the first “Catalog of Italian Red Wines – Wine Gotha,” featuring Brunellos from Biondi Santi with three stars, Fattoria dei Barbi with two, and Il Poggione with one. Within a few years, Brunello hectares grew to 470 with over 100 producers, reaching 693 hectares by 1980. The fragmentation among medium, small, and tiny winemakers, which would characterize the future of Montalcino wine, was already evident.

Giovanni Colombini, owner of Fattoria dei Barbi

Giovanni Colombini, owner of Fattoria dei Barbi

1970 - 1989: Brunello Drives the Recovery

At the start of the 1970s, Brunello production had already surpassed one million bottles (official data reports lower figures but is notoriously unreliable for those years), and it had a significant presence throughout Italy and major international markets. In Veronelli's 1972 second “Catalog of Italian Red Wines – Wine Gotha,” three Brunello wines were listed. By the third catalog in 1974, the number of producers grew to five, and in the fourth catalog in 1976, there were six. At that time, fewer than 100 Italian wineries exported quality wines, yet Montalcino already had about ten such producers. By 1978, Montalcino had the highest per capita income of any municipality in the province of Siena. By 1980, wine production experienced explosive growth, reaching 93 winegrowers, 693 hectares of Brunello, and 4,034,320 bottles produced (including Brunello and Rosso di Montalcino) almost entirely by local winemakers. In that same year, Burton Anderson, perhaps the world’s most renowned wine journalist at the time, described Brunello as Italy’s finest wine, stating that in some cases, it surpassed the prices of top French grand crus. Confirming the success, in 1985, two Montalcino wineries, Biondi Santi and Fattoria dei Barbi, were included by Wine Spectator among the world’s 100 most prestigious wineries during the first New York Wine Experience. Brunello had already become the high-end Italian wine generating the highest revenue—a title it would maintain for the next four decades. Its rapid growth, high prices, worldwide sales, and image success attracted the attention of Italian and foreign entrepreneurs who decided to invest in Montalcino. By the late 1970s, the first group of “non-local” winegrowers arrived, growing in the following two decades to represent roughly a third of both production and the number of producers. In 1984, Brunello became the first wine in Italy to receive the DOCG. Meanwhile, Rosso di Montalcino acquired the DOC, becoming the first fallback designation. This was a major innovation developed by the municipality and the president of the Brunello Consortium, Enzo Tiezzi. In 1988, the Municipality of Montalcino and the Brunello Consortium organized the Centennial Celebration of Brunello, an idea by Franco Biondi Santi, centered on the four bottles of Brunello 1888 from Greppo. This marked the first major media event for Italian wine, solidifying Brunello's international acclaim. Montalcino had become the affluent, small-scale capital of Italian wine—both provincial and dynamic, globalized with businesses of all sizes evolving and competing. It was a development with exceptionally high growth rates yet firmly rooted in ancient, vital traditions.

In 1984, Brunello became the first wine in Italy to obtain the DOCG

In 1984, Brunello became the first wine in Italy to obtain the DOCG

1990–2008: The First Golden Age of Brunello

The 1990 harvest marked the first great vintage of Brunello's “golden age,” with 2,536,274 bottles sold at prices often double those of 1989. In 1993, the Consortium president, Sante Turone of Caparzo, created “Benvenuto Brunello.” This event featured tastings of DOCG and DOC wines from nearly all Montalcino producers and was held at the picturesque Castello di Poggio alle Mura of Banfi. This was the beginning of “Anteprime,” a hugely successful communication format soon copied across Italy. The event attracted 200 journalists from prestigious global media outlets and resulted in thousands of articles. Within a few years, Brunello vineyard acreage grew from 1,260 to 2,100 hectares, while Rosso di Montalcino increased to 550 hectares. By 2000, Brunello sales reached 4,608,562 bottles—nearly double the figure from a decade earlier.

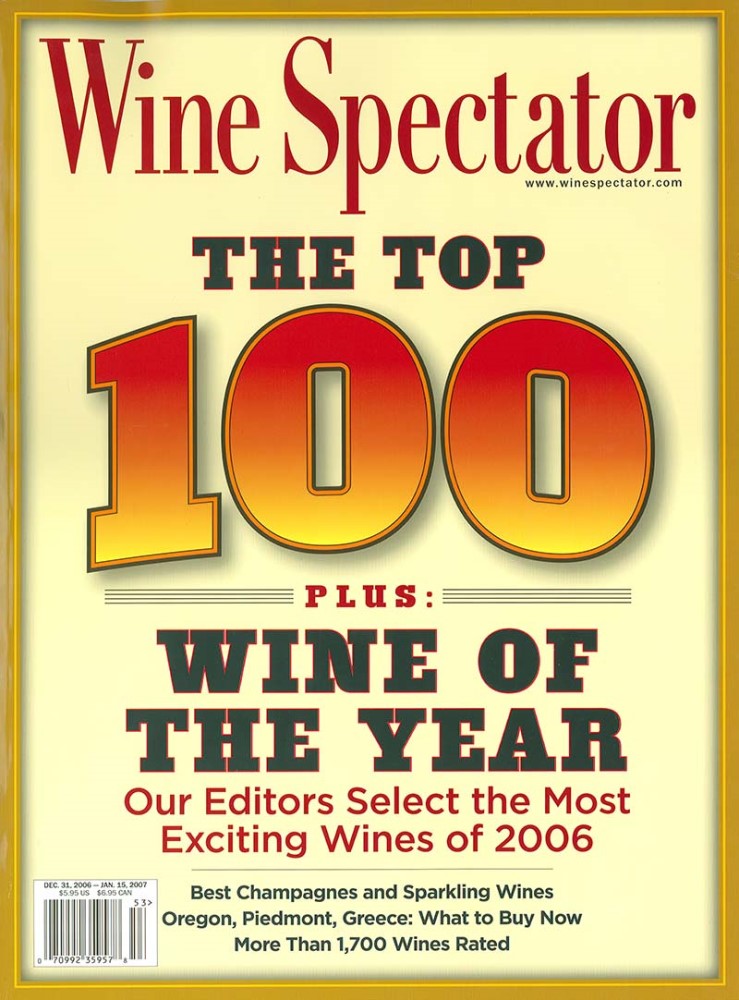

In 2002, the highly-praised 1997 Brunello was released, earning both exceptional sales and critical acclaim. The market was so captivated by the “vintage of the century” that it accepted dramatic price increases. By 2005, the Censis reported over 2 million tourists visiting annually, equating to 384 visitors per resident—the highest ratio in Italy. In 2006, Casanova di Neri's Brunello was named the world’s best wine by Wine Spectator, the pinnacle of numerous accolades awarded to over 100 Montalcino producers. By this time, there were more than 240 bottlers, selling 6,854,234 bottles of Brunello. From 1990 to 2008, both wine quantities and prices grew by an average of almost six percent annually. Brunello's reputation soared, and some brands gained global recognition. During these years, different wineries emerged as leaders in guide scores and wine journalism, with names like Soldera-Case Basse, Poggio Antico, Cerbaiona, and Casanova di Neri shining in their respective periods. During this time, the “Brunello” brand arguably became more significant than individual winery labels, likely establishing itself as the world’s most renowned collective Italian wine brand.

In 2006, Casanova di Neri's Brunello was named the world’s best wine by Wine Spectator

In 2006, Casanova di Neri's Brunello was named the world’s best wine by Wine Spectator

2009–2018: Fall and Rebirth

On September 11, 2008, Lehman Brothers collapsed in New York, triggering the global financial crisis. Montalcino faced multiple simultaneous challenges: the worldwide recession, the 1997 decision to increase Brunello production (boosting supply by 50% just as demand plummeted), and a criminal investigation into some wineries suspected of blending other grape varieties into Brunello. The “Brunello scandal” had devastating media consequences, with thousands of articles worldwide casting doubt on the integrity of Montalcino's winemakers—an annus horribilis. Bulk wine prices fell from €900 per hectoliter to €300, and bottle sales declined.

In 2009, Brunello stockpiles reached 47,216,400 bottles—an excess equivalent to 1.5 years of sales. Revenue for many wineries plummeted, but by 2012, branded bottle sales began to recover. Remarkably, Montalcino emerged from this harsh trial within six years, profoundly transformed yet without any Brunello wineries closing or being sold. The stringent controls implemented after the scandal had an unexpected result: they improved both quality and consumer trust. As a result, annual Brunello sales rose from 6 million bottles at the start of the century to nearly 10 million, with record-breaking prices. The severe 2009–2015 crisis pushed nearly all wineries to optimize production and adopt innovative technologies.

Monitoring extended to the fields, fostering more environmentally conscious practices, often organic or biodynamic. Almost all Montalcino vineyards are now grassed over, olive groves are well-maintained, and abandoned fields or farms have disappeared. Most Montalcino operators improved marketing and communication. The outcome was a stronger positioning for Brunello and more prominent recognition for Montalcino businesses. In 2018, on Wine Spectator, Casanova di Neri ranked fourth globally, and Altesino ranked eleventh; on Wine Advocate, Le Chiuse was second, Ciacci Piccolomini eighth, and Costanti thirteenth. As Friedrich Nietzsche famously wrote, “That which does not kill me makes me stronger.” Montalcino has created Italy's most profitable agriculture.

2019 to Today – Where Is Montalcino Heading?

No account of Montalcino would be complete without addressing its present. On January 1, 2017, Montalcino merged with San Giovanni d’Asso. The population rose to 6,043, and the territory expanded to 31,013 hectares. Agriculture employs 2,000 people, peaking at 2,600 during high seasons. Vineyards cover 3,480 hectares, of which 2,100 are registered for Brunello di Montalcino DOCG, 510 for Rosso di Montalcino DOC, 38 for Chianti DOCG, and 832 for Sant’Antimo DOC or IGT Toscana. Sangiovese grapes account for 2,750 hectares, representing 80% of the total vineyard area. Excluding the three largest producers, the remaining 300 businesses cultivate 97% Sangiovese.

From 2011 to 2019, many wineries were modernized, and high-quality tourist facilities emerged. Most notably, 887 hectares of vineyards were planted, bringing the total to 4,315—a 24% increase in eight years. Success has not concentrated production in the hands of a few: the 10 largest producers account for one-third of Brunello, the next 40 for another third, and the remaining portion belongs to smaller wineries. Montalcino residents own two-thirds of the vineyards, explaining the strong connection between the wines and the land.

Recently, about 5% of Montalcino’s vineyards, including historic brands like Biondi Santi and renowned labels like Cerbaiona and Poggio Antico, have changed ownership. Will success continue? Likely yes, as it stems from stable factors: the strength of the Brunello brand, minimal price competition, limited production capacity, and a growing global market for prestigious products. Here, quality and image take precedence over price, creating a virtuous cycle: product improvements delight customers and media, enhance the Brunello brand, and increase bottle prices. This generates more resources to further improve quality and image, perpetuating the cycle.

In 2020, the Brunello 2015 “record vintage” was sold; never before in wine history had so many wineries within a single denomination received so many perfect scores (100/100, 20/20, etc.). Then came COVID-19. In 2021, James Suckling and major wine publications crowned Brunello 2016. In Wine Spectator’s “Top 100,” two Brunellos ranked in the top twenty: San Filippo at third place and Caprili at sixteenth.

Montalcino continues to prove itself as something unique, dynamic, and adaptable—a play with the same cast of characters, yet constantly exchanging roles on a versatile and ever-changing stage.